Cantantibus organis. Two little words that created a myth which by the end of the sixteenth century was unstoppable, it was so appealing.

St Cecilia, a Roman Christian and noblewoman, died (unpleasantly) as a virgin martyr, with no obvious musical skills or interests. Well, actually, we don’t even know if she really existed, but around AD450 Arnobius the Younger, a monk living near Rome, assembled stories about her into an account, the Passio sanctae Caeciliae. According to this, an arranged marriage brought Cecilia into crisis, and during the wedding festivities ‘…while the instruments sang (cantantibus organis), she sang in her heart to the Lord alone…’

The obvious meaning being that she ignored music for higher things, and some depictions in art show exactly that: an organ and other instruments fall broken at her feet in Raphael’s painting, below.

But as the centuries progressed, the story turned on its head. The conventions of religious art (and the illiteracy of the population) in the 15th- and 16th-centuries required a symbol to individually identify saints, and the standard palm branch atrributed to a virgin martyr wasn’t sufficient when multiple virgin martyrs appeared in a single painting. So, for example, St Barbara gets a miniature tower, St Agnes holds a lamb (I’ll spare you the more gruesome ones) and Cecilia was given – yes, an organ, in a sort of wilful misappropriation and mistranslation of cantantibus organis.

In a Virgin and Child with Four Holy Virgins from the late 15th century, below, their symbols appear on rather lovely pendants around their necks. (Cecilia is top left.)

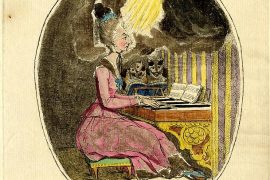

It didn’t take long for her to shift from being just a carrier of a symbolic instrument to a practising musician (mostly on the organ or other keyboard instrument, but also on the violin or lute), and as such she was enthusiastically adopted as a patron by musicians’ guilds and companies. Eventually she morphs into a sort of celestial session player, accompanying King David on his lyre along with a full orchestra of the heavenly host (below).

John A Rice’s new book St Cecilia in the Renaissance, The Emergence of a Musical Icon gives a definitive account of this evolution of a lesser martyr into celebrated muse and patron saint of music and musicians. He traces the development of the cult of St Cecilia through Christian liturgy, the visual arts and music, starting in northern Europe in the Middle Ages and moving to Italy, when an explosion of polyphonic vocal works were written in her honour by some of the most celebrated composers in Europe.

The book began with his studies, starting in the 1980s at the University of California, Berkeley, into Cecilian motets, and I have to admit skipping through some of the detailed discussion and comparative tables of structural analysis of words and music he includes at the centre of the book, which hold up the narrative for the less academic reader. But the book is generous with both musical examples and colour plates, and I greatly enjoyed reading the story of how her body was fortuitously discovered at the height of the Counter-Reformation, and how her Saint’s Day became a reason for making ‘great Musick’, not to mention a good excuse for beer, wine and feasting.

John Rice ends the story in Restoration England, as Cecilia becomes a muse rather than a saint, and Purcell writes his first great Cecilian ode Welcome to All the Pleasures. I didn’t really want the book to stop there, but I guess by then her iconic status was settled, and artists and composers simply drew on this, in varying degrees of realism or religiosity, through to the present day. Indeed, by the eighteenth century she was a familiar cultural reference for actresses, satirists and the rest of the haute monde: see Modelling the Muse : pretending to be St Cecilia.

Saint Cecilia in the Renaissance

Saint Cecilia in the Renaissance

The Emergence of a Musical Icon

John A. Rice

University of Chicago Press

ISBN: 9780226817101

$65

In the UK can be bought from all good bookshops, for example, Waterstones, or Blackwells, for around £52 (hardback)

feature image: a detail from of The St Bartholomew Altarpiece (c1500-1510) via A.Davey

Is Francesa Massey the daughter of Roy Massey? If so I can undestand the power of inheritance!

Not sure Peter! – I’ll have to ask her

What an intriguing post! Gutted that St Cecilia is not the music lover we imagined. Thank you

Yes, me too! Cecilia at the organ is such a powerful image, through hundreds of years of art. And one of the first grown up pieces of choral music I learned was Britten’s Hymn to St Cecilia, which I loved. Well, I’m just going to carry on believing….. 🙂