Putting aside for a moment the whole shaky foundation to St Cecilia’s identification with music in general, and organists in particular (for which see my recent review of John A. Rice’s new book), to mark St Cecilia’s Day this year I offer you some historical women cosying up to the pipe organ to impersonate the Muse, with varying degrees of success.

Firstly, Emma Hamilton, mistress of Lord Nelson, had artists lining up to paint her as all sorts of mythological personas – it was as good an excuse as any in the eighteenth-century for catching the likeness of an attractive female in a state of undress, while at the same time elevating both the character of the sitter and the status of the painting. She was painted as (a fairly decorous) St Cecilia twice. In both cases instruments are kept well to the sidelines as purely indicative props, so as not to detract from La Hamilton. Here’s the first pose of heavenly regard by George Romney – she looks like a girl caught artfully saying her prayers rather than an ecstatic visionary.

The second painting by Richard Westall probably dates from after Nelson’s death and has a more convincing look of saintly ecstasy, though any keyboard teacher would say her hand position could do with improvement.

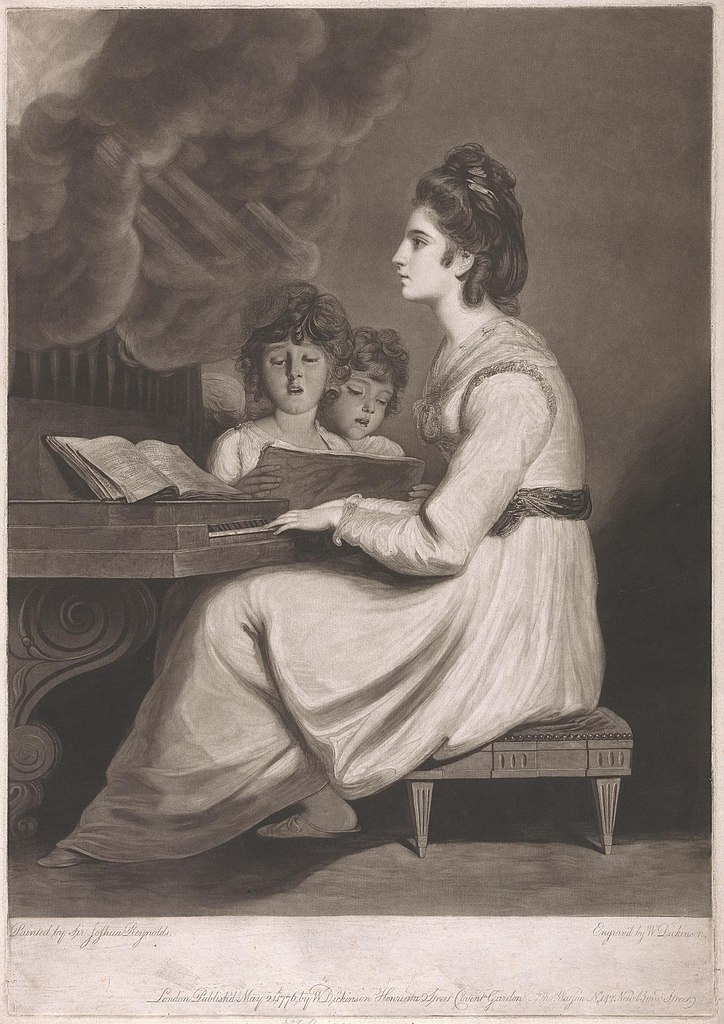

Mrs Robert Arkwright as St Cecilia (below) brings rather more religiosity to her impersonation, adding a halo, and celestial rays emanating from a gathering storm of clouds around her head. I warmed to Mrs Robert Arkwright when I discovered she was Frances Crawford Kemble, an actress of some renown, and part of the famous theatrical family, before her marriage. As such Robert’s family were dead set against her, but she became a successful hostess, charming the aristocracy while continuing to write music.

This painting hung over the fireplace in the family home, Sutton Scarsdale Hall in Derbyshire (and I wouldn’t mind a painting of me as St Cecilia at the Organ over our fireplace, to be honest). This former Georgian Mansion is now a Grade 1 listed wreck sadly, in the care of English Heritage, reduced to a derelict shell by asset-strippers in the early twentieth century.

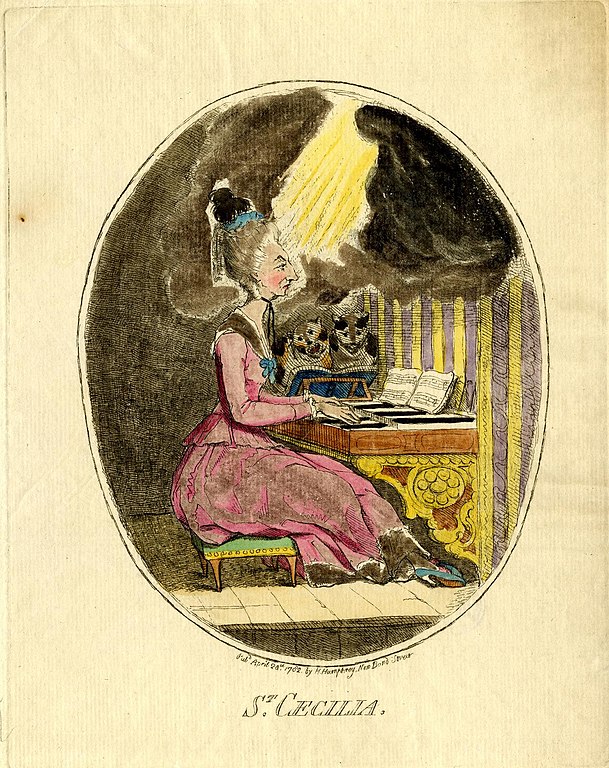

Joshua Reynolds considered his painting of Mrs Elizabeth Linley Sheridan as St Cecilia as ‘the best picture I ever painted.’ Elizabeth Anne Linley was said to have one of the loveliest voices in Britain, although her husband, the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, didn’t allow her to perform in public. The portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1775 and a print after it was published the following year, and much copied. The painting itself is now in the National Trust’s Waddesden Hall, but not in good condition having been damaged by historical attempts at restoration and cleaning. So the print, below, is a valuable record of the original.

The pointers towards sainthood have been awkwardly executed I feel: an elegant society lady in her salon with two placid child attendants, this St Cecilia appears unperturbed by apocalyptic clouds pouring out of the organ in front of her face (which would certainly worry me).

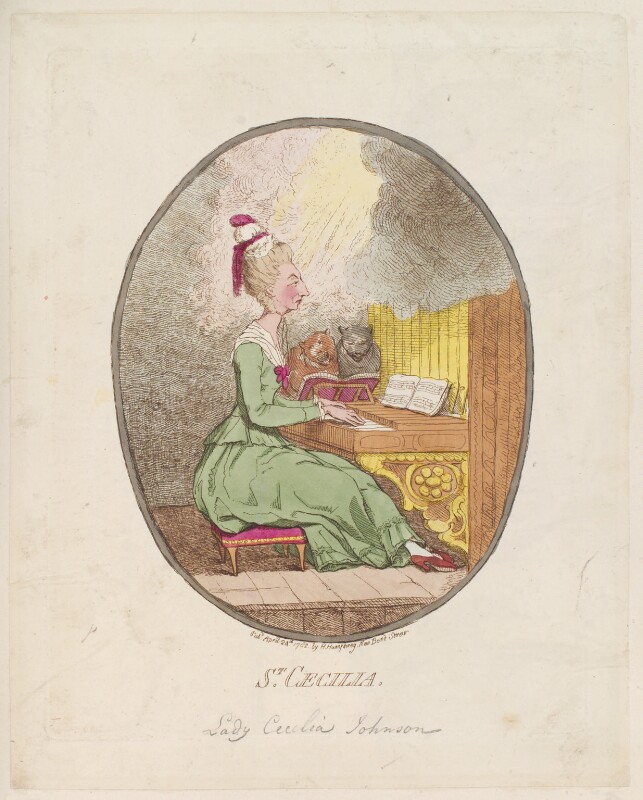

Having been exhibited at the Royal Academy, the painting was obviously the talk of the haute monde, known well enough for caricaturist James Gillray to guy it a few years later, in a print satirising a contemporary society lady, a Mrs Cecilia Johnston (below), where the two angelic beings have been replaced with yowling cats.

Gillray caricatured Lady Cecilia Johnston in at least eight different prints, but I can’t find out why he was quite so spiteful. She seems never to have been involved in any social scandal, and her sole fault, if it could be called that, appears to be a very singular facial profile that called out for parody. After being the centre of the British community in Menorca where her Lieutenant-General husband was stationed for ten years, she perhaps had an inflated view of her own importance on returning to England. Some contemporaries remembered her as vain, proud and a little absurd. Gillray caricatured her several times in musical settings, so perhaps she affected pretensions towards musical appreciation or ability.

Finally here’s something nice to listen to on St Cecilia’s Day, 22 November –

A Spotify playlist I’ve put together of music from the 16th to 20th centuries written in tribute to St Cecilia: Purcell, Handel, Howells, Britten, Liszt and others.

It previews below, and displays a link through to Spotify to listen in full. You can create a free Spotify account if you don’t already have one.